Let’s delve into all there was to see, hear and discuss.

We, the Gira Architecture editorial team, were in Venice for the opening weekend of this year’s Architecture Biennale and we can now report exclusively on our highlights from the various exhibition areas.

We can reveal that intelligence can take many forms – and some may surprise you.

But first let’s start with the basics – what’s the theme of this year’s Architecture Biennale?

The Architecture Biennale 2025 is titled “Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective”.

The 19th Architecture Biennale explores the interfaces between people, nature and technology. Curator Carlo Ratti – architect, engineer and director of the MIT Senseable City Lab – presents a vision of urban space as a collective system. “Intelligens” stands for the interplay of natural and artificial intelligence – and for the potential of collective knowledge in architectural design.

The Architecture Biennale 2025 is spread across two central locations: numerous countries are showcasing their national contributions in their own pavilions in the Giardini, while the main international exhibition and other national exhibitions are on display in the Arsenale.

However, the Architecture Biennale does not stop at the gates of the Arsenale and the Giardini. Numerous “collateral events” and other national exhibitions are being held throughout the city of Venice, complementing the programme and offering additional perspectives on the theme. These broaden the architectural discourse and invite visitors to experience the city itself as part of the exhibition and to make further architectural discoveries off the beaten track.

The most significant exhibition

highlights at a glance

The Arsenale site

The Arsenale is one of the two main exhibition venues of the Architecture Biennale, located within a former shipyard. It houses the central exhibition, brought to life by curator Carlo Ratti, which reflects and questions the title of the Biennale in a variety of thematic areas. In addition to the main exhibition, the Arsenale also hosts numerous national exhibitions.

Main international exhibition

The first room of the main exhibition curated by Carlo Ratti in the Arsenale left a lasting impression on us. The installation “Terms and Conditions” confronts visitors with the effects of our comfort habits. In a darkened, mirrored room, air conditioners hung from the ceiling, their warm exhaust air directed straight into the room. Below sat a water basin that intensified the heat and the reflective surfaces. The piece creates a feeling of physical discomfort and reflects the often overlooked consequences of our energy consumption.

A particular highlight in the outdoor area was the installation by Norman Foster + Partners, created in collaboration with the Norman Foster Institute. It deals with future water mobility concepts – including the opportunity to test innovative watercraft. The expansive installation combines research, design and technology and addresses the role of infrastructure in climate-conscious urban development.

Another remarkable installation on the site, entitled “Laguna Viva”, offered visitors the opportunity to drink fresh espresso made from filtered lagoon water and was awarded the Golden Lion for Best Participation by the international jury of the Architecture Biennale. A specially developed filtration system supplies the coffee machine with treated water directly from the Venetian lagoon. We tried it, of course, and can say that the espresso was excellent – perhaps tasting even better thanks to the unique atmosphere of the Architecture Biennale.

Moroccan pavilion

In addition to the extensive main exhibition, we also considered the Moroccan pavilion at the Arsenale site to be one of the most impressive contributions to the Architecture Biennale. Entitled “Materiae Palimpsest” and curated by Salima Naji, it explores the cultural and architectural potential of mud brick construction. The exhibition shows how traditional Moroccan techniques can be combined with contemporary digital methods, focusing on the relationship between craftsmanship, materials and people. In an immersive spatial experience, the pavilion brings the sustainability of local resources to life.

The Giardini site

The Giardini site is reserved exclusively for the contributions of the participating nations. A total of 26 national pavilions present their perspectives on this year’s theme, each with its own curatorial approach and often impressive spatial design.

German pavilion

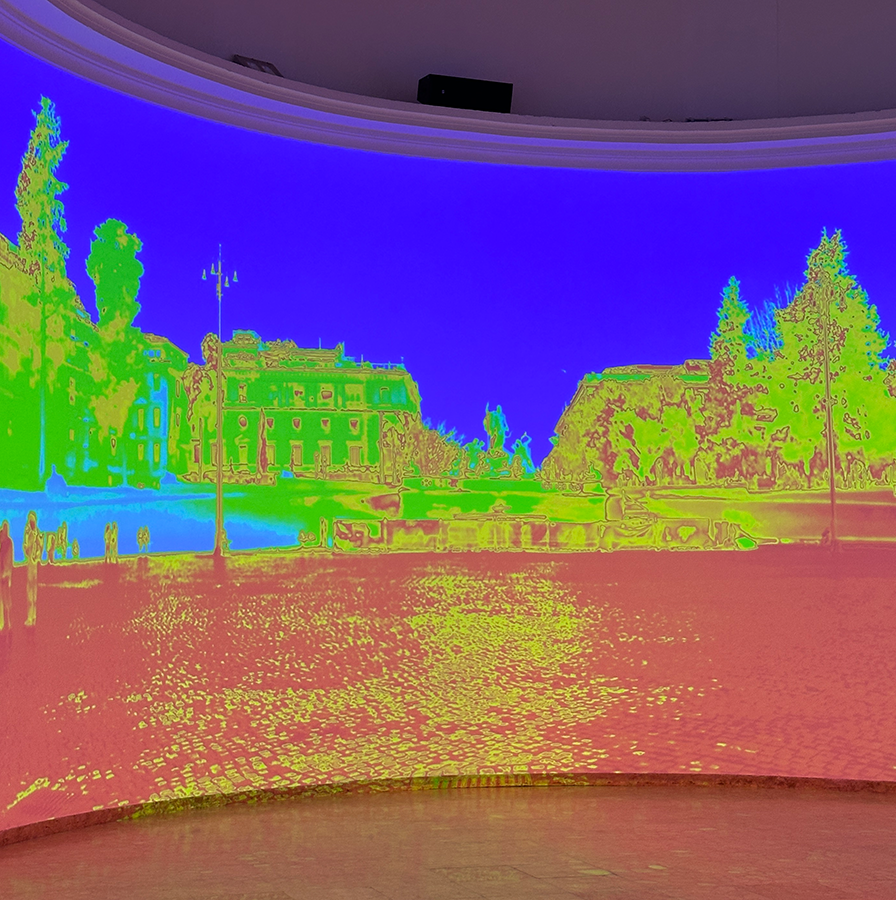

A prime example is the German pavilion, curated by the “Stresstest” team. Under the title “Open for Maintenance / Open for Transformation”, they have turned the pavilion into a space for experiencing and engaging with climate resilience and transformation processes in urban development. Particularly striking is a visualisation of possible measures to reduce our CO2 emissions.

The contribution was curated by Anh-Linh Ngo, Franziska Gödicke, Christian Hiller and Melissa Angela Alemaz Koch (ARCH+), Anne Femmer and Florian Summa (Summacumfemmer) and Juliane Greb and Petter Krag (Büro Juliane Greb).

Canadian pavilion

The Canadian pavilion, on the other hand, explores a completely different theme. Under the title “Archi-féroces”, Lateral Office – led by Lola Sheppard and Mason White – transforms the space into a living laboratory, questioning how microbial life can shape architecture. Inside, impressive living sculptures reveal how intelligently this type of bacteria can help shape our environment.

Serbian pavilion

Circularity takes centre stage in the Serbian pavilion. Curated by Marija Mojasevic and Luka Cakic, the space – wrapped entirely in woven textiles – initially appears sculptural and still. But as the Biennale progresses, spindles mounted on the walls slowly reveal its deeper meaning. Entitled “Woven Structures”, the installation continuously unravels and rewinds the fabric throughout the entire Biennale. Powered by rooftop and façade-mounted photovoltaic elements, the mechanism embodies the concept of circularity – not just thematically, but also in practice. By the end of the Biennale, the material will remain intact and ready for reuse.

Polish pavilion

In these difficult times, marked by global unrest, the Polish pavilion made a lot of people smile. With “Panic Room”, Jacek Sosnowski and Zofia Jakubowicz use architecture to offer a witty yet critical take on the anxieties of modern life. A fire extinguisher – placed in fear of fire – is presented like a holy artefact, while an overwhelming number of safety signs around the emergency exit challenge our perception of architecture and the regulations that shape it.